By Ivan Vazquez, Farmworker Association of Florida & Magha Garcia, Boricua Organization of Ecologic Agriculture of Puerto Rico with a special contribution by Anne Frederick, Hawaii Alliance for Progressive Action

History and Context

Hawaii’s diverse natural scenery, warm tropical climate, abundance of pristine beaches, oceanic surroundings, breathtaking landscapes and active volcanoes make it a popular destination for tourists, surfers, biologists, and volcanologists. But above all the natural beauty Hawaii has to offer, its people are what stand out for me, for they are warm, welcoming and resilient and they are the representation of Aloha Spirit, which is the coordination of mind and heart within each person. This spirit brings each person to the self. In this spirit, each person must think and emote good feelings to others. These attributes constitute the Hawaiian identity.

Hawaii is a volcanic archipelago situated in the north Pacific Ocean approximately 2200 miles away from the U.S main land. Hawaii has a rich history, culture and traditions and its people have a strong connection to the land. Historically, Hawaiians shared the stewardship of the land and it was everyone’s responsibility to care for it, just as it is the case for many other island inhabitants whose resources are limited. That changed in the 17th century, when Europeans began to settle in the islands and spread their ideas and philosophies and religion.

The state of Hawaii was the last state to join the union in August 21, 1959. However, this annexation still is seen with resentment by most native Hawaiians, since US troops invaded the sovereign kingdom of Hawaii, kidnapped their queen, banned the natives from speaking their native tongue, disrupted their farming practices, and almost wiped out their culture.

Hawaiians are wise and loving, and proud of the culture and traditions. during our visit there, Magha Garcia and I felt very welcomed and embraced by all the people we met. the locals proudly showed us their traditional foods such as, Poi and Ulu. Poi is a Hawaiian dish made from the fermented root of the taro, which is boiled then pounded to a paste. Ulu is Hawaiian variety of breadfruit. The traditional methods for preparing breadfruit is peeled then steamed or boiled, then pounded into paste that has the consistency and texture of mashed potatoes.

Last August, my colleague Magha and I participated in a learning exchange visit to Hawaii to understand the island’s past and present struggles. Also, this visit had the purpose to build and strengthen the relationships between the U.S. Food Sovereignty Alliance (USFSA) and organizations in the Hawaiian islands such as HAPA.

July 26th, 2018

This trip to Hawaii began July 26, 2018. This day was mostly for traveling, sleeping accommodations, registrations and general details of the conference. For more information of the agenda please visit: https://www.hawaii.edu/sustainability/saea-agenda-overview/

July 27th, 2018/ Day 1

In Camp Pālehua, our day started at 5:30 am as Magha and I, along with a very diverse group composed of around thirty-two people from different parts of the country, of various age groups, gender orientations, ethnicities and countries of origin gathered, together facing the the east as instructed by Dr. Manulani Aluli Meyer or Manu, as she likes to be called, to receive the sun as it rose from the horizon with the traditional Hawaiian sunrise chant called “E Ala E”. Manu beautifully directed the chanting in a harmonious way.

Ho’opuka E-Ka-La Ma Ka Hikina

Ai, Ai, Ai.

Ho’opuka e-ka-la ma ka hikina e

Kahua ka’i hele no tumutahi

Ha’a mai na’i wa me Hi’iaka

Tapo Laka ika ulu wehiwehi

Nee mai na’i wa ma ku’u alo

Ho’i no’o e te tapu me na’ali’i e

E ola makou a mau loa lae

Eala, eala, ea. A ie ilei ie ie ie.

He inoa no ma ka hikina

While singing this powerful chant, we were honoring the indigenous Hawaiians roots, acknowledging their ancestral lands and their connection to the natural elements. While we were singing, I instantly felt a strong connection and appreciation of the ancient indigenous traditions. It is no surprise that native Hawaiians were so attuned with nature. As we participated in this ceremony, we were convinced that this conference would be memorable.

After the chatting and the offering ceremony, Manu talked about the importance of indigenizing the school system as an important step to phase out different aspects in our modern society, but primarily to affirm our current relationship with the land (Aina) as the source that supports all life. For a more detailed explanation, please click these following links here Mobilizing Sustainability in Education.

Once the sun was out, we were asked to walk to the dining room, which faced directly toward the Pacific Ocean. There we were served a lovely breakfast before heading to the University of Hawai‘i – West O‘ahu to participate in the 2018 Sustainable Agriculture Education Conference.

The Themes for this conference were:

Theme I -Decolonizing the Food System: Feeding ourselves

Theme II – Indigenous Knowledge, Power and Pedagogy

Theme III – Living Traditions, Living Economies: Towards Self- Determination, Resilience and Equity in our Food Systems

SAEA Conference opening at UHWO

The official opening of this conference started with students, aunties and uncles (terms of endearment to the elderly) singing E Hō Mai. This chant is used as a way to enter the mind into a state of sacred ceremony, thanking mother earth for its boundless supply of food for our body and appreciating the spirits of the elders for guiding us through this journey that we call life.

The chant (oli) is translated as:

“Grant us knowledge from above

The knowledge hidden in the chants

Grant us these things.”

lyrics:

E Hō Mai

Ka ‘ike mai luna mai ē

I nā mea huna no’eau

O nā mele ē

E hō mai, e hō mai, e hō mai ē

In a sense, this chant is calling upon their Hawaiian spirit guides, angels, and ancestors above to share their wisdom with the people to guide humankind on their path. This chant is a bridge to connect us and root us with our ancestors and our history.

July 28th/ Day 2

Hale

On this day, we visited a fascinating farm called Ka’ala Farm which serves a multipurpose complex: as an ancient agricultural farm, restoring and producing kalo as their Hawaiian ancestors did for centuries and as a Cultural Learning Center, where learning comes alive for thousands of school children in their hands-on science programs every year. It is a cultural kipuka, where Hawaiian traditions are practiced daily to make people and communities stronger.

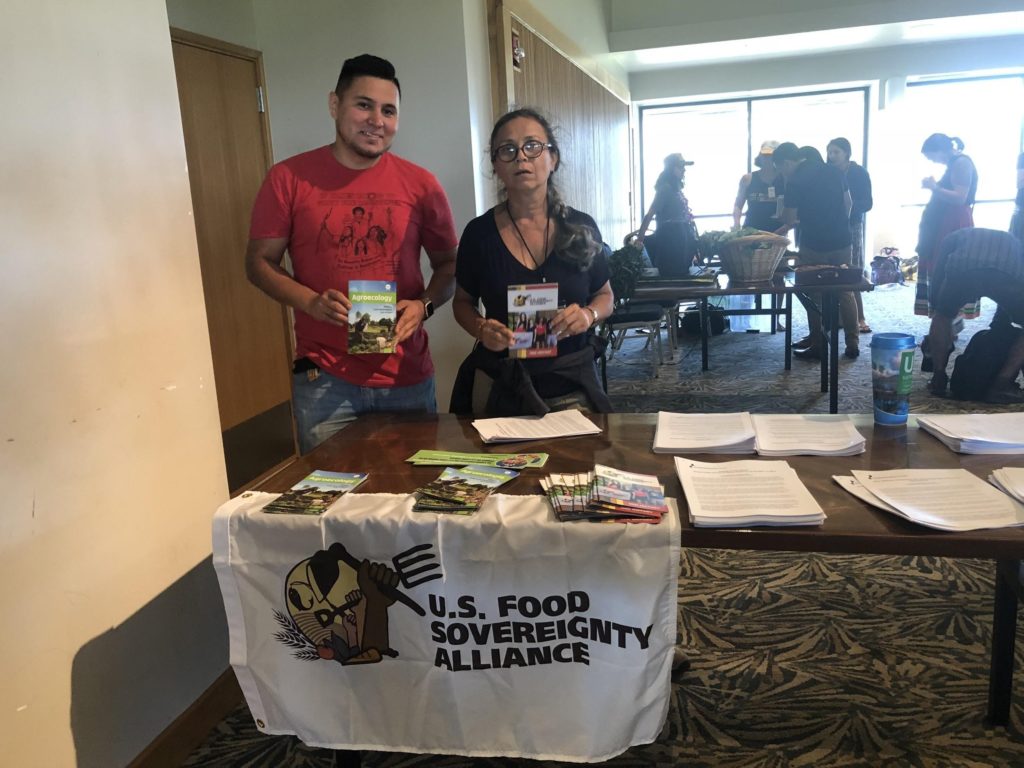

Later in the afternoon, we presented our workshop entitled Political Education and the People’s Agroecology Process. Around 25 people participated in our workshop, where Magha and I explained the two most important components for USFSA’s movement: agroecology and food sovereignty. Most of our audience was familiar with those two terms. I explained how we as the USFSA and The Farmworkers Association of Florida (FWAF) are fighting to change the food system; FWAF at the grassroots level and the USFSA as a national level. Both organizations are working in one accord to end poverty, rebuild local food economies, and assert democratic control over the food system in order for people to have the right and access to healthy, culturally appropriate food, produced in an ecologically sound manner. We also illustrated how political education helps us shape our Alliance and amplifies our work.

July 29th/ Day 3

Sunday was the closing day. We began this day as it is traditional in Hawaii – with a chant. We participated in plenary sessions, where the speakers summarized the highlights of the conference. All the speakers reiterated the main goals of this convening which are: first, to strengthen our communication between Hawaii and the mainland USA; second, to amplify the urgency of indigenizing our agriculture system in a way that creates a symbiotic relationship with the environment, meaning to protect our planet by becoming more self-sustainable; and lastly, to recognize the need to respect and honor farm workers, including by not exposing them to harmful chemicals and to adequately monetarily compensate their arduous labor with living wages that reflect their effort.

Later that day, we headed to the airport to fly to Kauai, as it was part of our visit to stay with our host Anne Frederick, Executive Director of the Hawai’i Alliance for Progressive Action (HAPA). Magha, Anne and I introduced ourselves we briefly stated who we are, what organization/alliances we represent and the type of work that we are involved in. We also engaged in meaningful conversations about agriculture, pesticides regulation, immigration, labor exploitation and among many other subjects.

July 30th/ Day 4

We visited and volunteered at Kumano I Ke Ala, a nonprofit taro farm located in Waimea on the west side of Kauai. There we met the program director, Kaina Makua, who explained to us the history of the organization and its mission. Kaina introduced us to his interns, a mixed group of around 12 boys and girls. The young people were eager to share their knowledge and experiences as Magha, Anne and I helped pull and cut vegetation to clear the water channel.

Taro is locally known in Hawai’i as kalo. Kaina also explained to us that to Native Hawaiians, kalo is supreme in importance—it is defined in the Kumulipo, or Hawaiian Creation Chant, as the plant from which Hawaiians were formed. When the first voyagers arrived on the shores of the Hawaiian Islands many centuries years ago, kalo was one of the few sacred plants they carried with them.

July 31st / Day 5

On Tuesday, Magha and I met with Jeri DiPietro from Hawaii Seed. Jeri drove us around in her pickup truck to the west side of the island to witness the devastation that agrochemical test fields have made on the people’s health and the environment. Magha and I were shocked and indignant to see that the test fields are literally steps away from a school’s backyard where kids play during recess. Parents were in a difficult situation; they had to make a tough decision whether send the kids to school to learn or deprive them from their education. That is when the people began to organize themselves to demand the companies to cease operations. After a many meeting, rallies, marches and call the people won this battle and the rescued their children from the long lasting neurological effects that exposure to this chemical causes.

The Toxic Tour with Jeri DiPietro from Hawai’i Seed. View of the affected area by corporations in Kaua’i (Photo by Ivan)

In the evening, Jeri, Magha and I met at a local restaurant where we met up with the HAPA (Hawai’i Alliance for Progressive Action) Kauai team, including Fern Holland, Anne Frederick and HAPA’s board director, Gary Hooser. Jeri, Fern and Anne shared with us some important details on how they were able to mobilize people to take a stand against Monsanto to be able to win their latest policy victory, banning the neurotoxic pesticide, chlorpyrifos. Gary Hooser spent 8 years in the Hawaiʻi State Senate. Gary gave us some useful and insightful information about ways to maximize the advocacy work on pesticides and food sovereignty that we are doing in our particular areas and how to leverage our state legislature to gain political victories.

August 1st/Day 6

Magha, Anne and I visited Moloa’a Organica’a one of the largest organic farms in Kaua’i run by Ned Whitlock and his Marta Whitlock. Ned has always been a farmer even before moving to Hawaii from the continental US more than 20 years ago. Ned grew up in a farm in the Midwest and he always had a passion for farming which is shown in the quality of produce they harvest. Marta is originally from Chile, she migrated to the US over 20 years ago.

Ned and Martha happily shared the story of how they met and how after visiting Hawai’i they fell in love with the beautiful landscape and the decided to leave everything behind and embark in a new journey in Hawai’i to fulfill their dream of farming. They face many difficulties and adversity when they arrived but they were persistent and now their hard work is paying off, Ned and Martha are one of the largest organic growers for the islands of Hawai’i, where unfortunately most of the food is being imported but Ned and Martha are dedicated to make Hawai’i more self sustainable. They were both was very glad to show us around their family’s farm. They eagerly explained to us the process of how they make anaerobic compost which is submerging the food scraps in a covered water barrels and letting them decompose until the liquid is odorless and full of nutrients.

The Whitlocks certainly take great pride and responsibility for the food they grow and the stewardship of the land that is why they use agro ecological methods and they are committed to produce zero waste and provide locals with fresh ecologically responsible food has been their their farm’s mission.

Far back left-right Martha, Ned, Ivan; front left -right Anne and Magha. Volunteers at Waipa Foundation (Photo by Ivan)

August 2nd/Day 7

On Thursday, Magha, Anne and I visited Waipa Foundation. Waipa Foundation, for over 20 years, has worked with the community to manage the 1,600 acre ahupua’a of Waipa, located on the north shore of Kaua’i. Waipa is a place where folks can connect with the ‘aina (that which feeds us – the land and resources), and learn about Hawaiian local values and lifestyle through laulima (many hands working together). Waipa’s long history and commitment to connect people with the ‘aina has made this organization so successful and greatly treasured by the community.

The three of us had the pleasure to make poi alongside the locals and visitors that came from as far away as France and Japan and the United Kingdom. Poi is a Hawaiian dish made from the fermented root of the taro, which has been boiled and pounded to a paste. This dish is believed to have healing properties because of the high content of probiotics. In Hawaiian mythology Poi is sacred and it is believed to have been created as a result of the story of Hāloa that brings us to the beginnings of the Hawaiian people. Wākea, the skyfather, and Ho’ohōkūkalani, descendent of the celestial bodies, fell in love and together had a child. But the baby was stillborn, so the deities buried him on the side of their home – the side of the morning sunrise.

From that very spot where the gods buried their baby boy, a plant began to grow. This plant, whose heart-shaped leaf trembled in the breeze was the first kalo (taro) plant. The kalo plant was given the name “Haloanakalaukapalili” and he was loved.

Native Hawaiians are very protective of their Kalo they each family typically will only grow one variety of Kalo which most has been passed down from generation to generation. Native Hawaiians take pride in their kalo plant because it represent the knowledge that their ancestors have passed down from generation to generation.

August 3rd/ Day 8

For out last day in Kaua’i, Anne took Magha and me to a fish pond restoration project called Mālama Hulē‘ia. This project is run by a voluntary non-profit organization dedicated to improving key parts of the Nawiliwili Bay Watershed on Kaua‘i by eliminating an alien and highly invasive plant species and the reintroduction of native plants. We witnessed first hand the devastation that causes to the environment and the livelihood of natives occurred as a result of the irresponsible actions of corporations and the lack of government enforcement of environmental protections.

We commend this organization for endeavoring in the enormous task. We are very thankful for their commitment to the service of their community by restoring their ancestral way of life.

Conclusion

During our time in Hawai’i, we had the privilege to meet some of the most incredible people who are doing some some terrific work in their communities. Whether their work is through popular education, advocacy, grassroots organizing and civic engagement all those people have been necessary for Hawaii’s victory in banning chlorpyrifos. These people are brave warriors who are the resistance against capitalist agribusiness that prefer profit over people. These corporations are negligent about the negative impact that their bad agricultural practices have in the environment and the farmworkers. In addition to their mismanagement of the land farmworkers too often are not able make ends meet.

We commend Hawaiians for their extensive work and constant dedication to restore Hawai’i’s food sovereignty and ancient agroecological farming after centuries of colonialism. We are thankful for their bravery and we admire them as pioneers in the quest for a better world where farmworkers are treated with dignity not being forcibly exposed to deadly chemicals and poor working conditions; a world where mother earth is treated, honored, and revered, and not coerced to produce food that lacks nutritional value and where most of the food ends up being wasted, instead of going in the bellies of those who need it the most.